The Cure is in Canada: Grants to Cuba

Striding, striding, striding, striding…

It sounds a lot like striving.

And that’s all a man can hope to do in this world, anyway.

In my life, my striving, lately, has boiled down to striding. I say this word repeatedly, in rhythm to my footsteps, for long hours at a time.

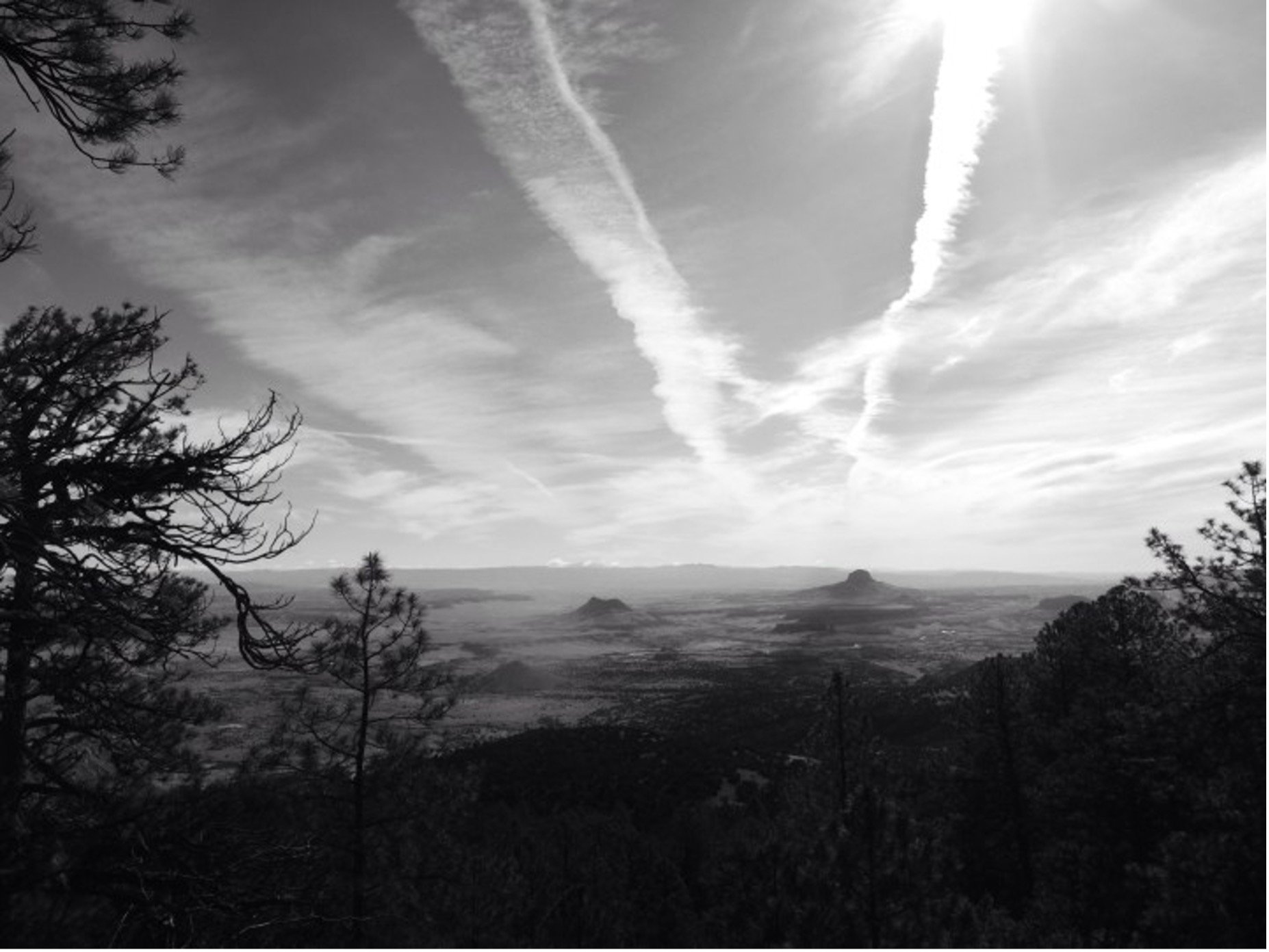

This past week we levied our striving on Mt. Taylor, on the mesas between Grants and Cuba, on the Rio Puerco river valley, over Mesa Chivato and Arroyo Chico and much of the San Mateo Mountain range. We strode adjacent to El Cabezon — Spanish for the Big Head — a fat volcanic plug that sits smack in the middle of a fat volcanic basin. We strode along deteriorating sandstone bluffs, on a trail hugging ridges, tracing a path up and down and around a field of strangely-eroded rock forms; and we exited, finally, in a valley of deep-green, healthy, hearty sagebrush – a New Mexican sage valley fit to rival any of those in Wyoming’s Shirley Basin.

New Mexico: A land of surprises.

One-hundred-and-fifteen miles in scizophrenic weather: snow, rain, sleet, hail, sunshine.

“I’ve had more weather in New Mexico than I had on the entire Pacific Crest Trail,” Memphis told me.

New Mexico: A land of surprises, indeed.

On day 2, we summitted Mt. Taylor, an 11,300-foot stratovolcano, just as a snowstorm hit the peak. Chimi and I beat Memphis to the top. It was too cold to wait, so we broke for lower altitudes, bracing against the wind, leaning like the krummholz, who pick awfully brutal places to live.

Partway down we consulted the map and waited for Memphis. When he came off the snow slope, out from under the tunneling trees, he waved happily at us – Chimi and I, wet and trembling and cold.

“I don’t know how he does it,” Chimi said as Memphis approached. “Look at him. He’s wearing shorts. No hiking poles. His rain jacket doesn’t even stay dry.”

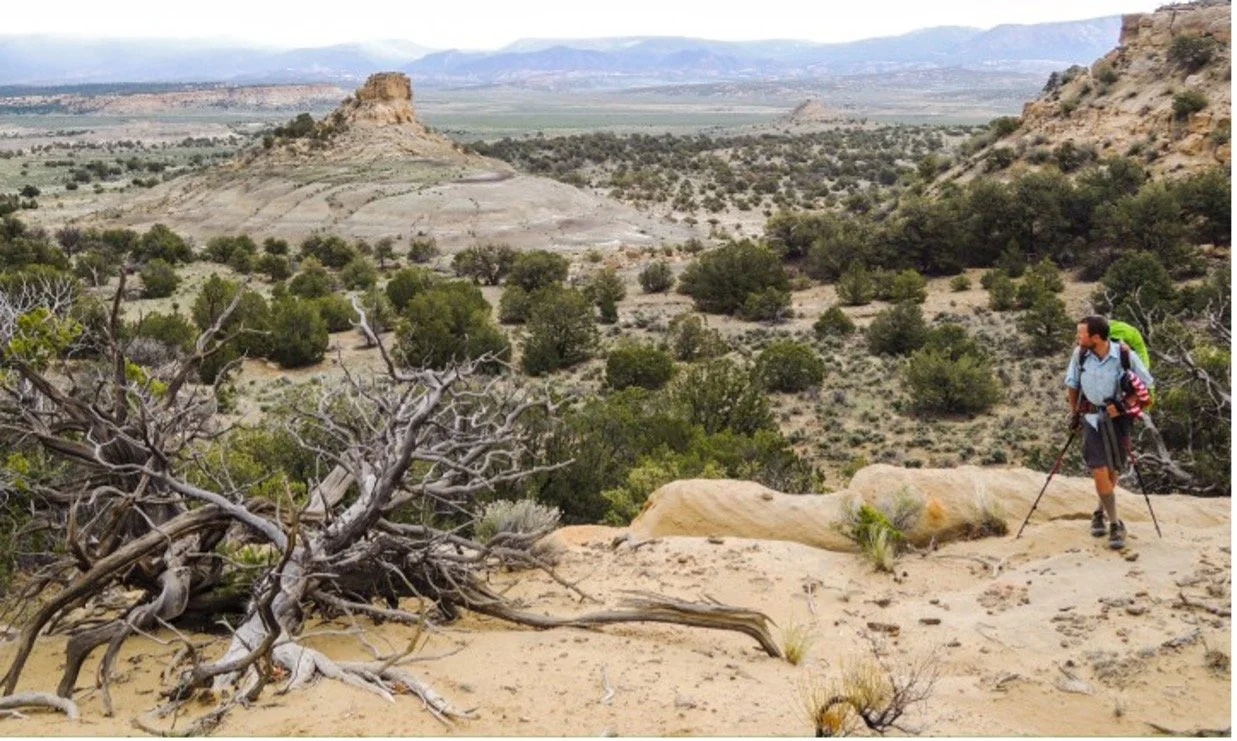

A hearty soul, that Memphis. Here’s a picture of him:

When we reached the foot of Taylor, snow drove us into a Ponderosa grove, where we dispersed and camped early.

Night fell. Hail smacked loudly on my tent, a machine-gun patter, a sound like hand fulls of sand thrown repeatedly against canvas. The bottoms of the walls of my tent are lined in mesh, and the last image I had before sleeping was of hail pellets piling up outside my vestibule.

I woke in the morning and it was sleeting and Chimi hollered across the grove:

“You awake?”

“Just woke up.”

“What do you want to do?”

“Should we walk?”

“I dunno.”

“What are you doing?”

“I just had coffee.”

“I’m gonna do that, too.”

We broke camp later, during a lull in the storm. Memphis reported feeling nauseated. It began to snow again, harder than the night before. I paced along behind my friends, watching snow and hail glance off their shoulders. We rendezvoused for a talk and asked Memphis how he felt.

The nausea persisted, he said.

“Let’s just keep walking,” I suggested.

“Walking is the medicine for everything out here,” Chimi said.

And Memphis agreed. “The cure is in Canada.”

We trudged for more than 20 miles on a muddy road beneath a bleak, formless sky. A boggy, soggy, snotty road, like walking upon a thin film of soup. Soupwalking, it makes your feet heavy. It makes the sound: squish, squish, squish, squish. Mud accreted on Chimichanga’s soles to the extent his shoes looked broad as paddles.

Duckwalking. Soupwalking. Memphis soldiering on through nausea, we walked because that’s all we could do, sure; but I think we also walked because we wanted something else. Something abstract. A hard-to-name yearning. A desire shared by all Americans. That is the desire to progress, to become something greater, to move forward.

And so we beat on, three hikers against the muddy road, borne back ceaselessly by the northern New Mexican winds.

That evening we took water from a spring called Ojos de Los Indios, Eyes of the Indians, a spring way down deep in an eponymous canyon. The rockwalls were maroon, mauve, blue-gray — colors deepened by the saturation of precipitation. I stood at the canyon’s rim after cameling up with water and watched as a cloud rolled into the valley and began unleashing torrents of hail, sheets of it pealing off the bottom of the boiling, roiling cloud, sweeping across the canyon, glistening in the slant-light of the setting sun, they were coming for me, the sharp, sweeping little hail pellets — I could count down the yardage — 30, 20, 10 yards to impact — and I just stood there, moored by the beauty of that moving spectacle, and pulled my hood off my head, and let them come, let the hailstorm envelope me and let the ice pellets bounce directly off my face, and there was something absolutely thrilling about abiding in the mercy (or mercilessness?) of the elements. Something stimulating about the roughness of it all. The sting of it. A raw experience. Unmediated.

By the next day, the weather was lovely. Sunshine and white cumulonimbi. Clouds like a great white armada set sail for Colorado. And Memphis felt fine, too. A beautiful thing about life in most places is you can expect more good days than bad.

After crossing a Mesa called (I think) Chavez, flat as a soccer pitch, we topped out at a vista of the Rio Puerco river valley. A 2,000-foot descent with a view of sandstone buttes and bluffs and precipitous escarpments, the cliffs of which tapered out into skirts of shattered stone. Quintessential American West. The background to a poster of a Clint Eastwood movie. A volcanic river basin, lined to the north and east with sandstone bluffs. And these bluffs were amazing. They looked exactly like a gargantuan fortress, the tan color of desert sands, complete with the battlements of a Medieval castle: parapets and turret towers and crumbling ramparts. We crossed the valley, fording Arroyo Chico (a little stream the color of coffee-with-cream) and came right up to the walls of this sandstone fortress. I had half a mind to find the drawbridge, give it three sturdy raps, and ask those dwelling within: “Would you let us inside, please? Teach us your mysteries?”

We climbed more high mesas with views dominated by the blockhead: El Cabezon. El jefe, mi carnal, it seemed to pan on the horizon as we perambulated, lording over everything in the valley. I’m all but convinced Cabezon knows at least some of this basin’s secrets. The myths hidden in the depths of this high desert.

The Navajo incorporate El Cabezon, Mt. Taylor and El Mailpais, which we previously traveled upon, into an interesting legend. As the story goes, an evil giant lived on Mt. Taylor, terrorizing the good people of the valley. Two Navajo demigods, known simply as the Hero Twins, climbed the mountain and decapitated the giant. The blood flowing from the slain giant’s veins formed El Mailpais lava flow. And the giant’s hardened head is what we now call Cabezon. Pictured below:

Cabezon’s geologic history is equally as rich. Magma solidified in the neck of an ancient volcano, forming a plug. Over the centuries, the softer rock of the greater volcano eroded away, leaving the hardened volcanic rock towering over the valley.

At one point on the third day we got a little water from a spring called Ojo Frio. As a water source, Ojo Frio wasn’t too appealing. It was basically a hole in a mud pit. For this reason, we didn’t tank up with a full load of water. Meanwhile, we missed a note on the map explaining this was the last water source for more than 20 miles. We cruised through the hot basin, got thirsty and eventually realized our mistake. The nearest possible water source was at a spot on the map marked with a note that said “new freeway.”

Holding out hope, we journeyed in the heat for 22 miles and arrived at the spot labeled “new freeway” to find a dry dirt road in the middle of nowhere. Thirsty and exhausted, the three of us dropped our packs and lay in the road.

So there we were. Three grown-ass men lying flat as pancakes in the road.

“We’re blocking traffic,” I said. “Maybe it was a congressman’s pork project.”

We were staring at the sky. The vultures.

“It’s the road to nowhere,” Memphis remarked. “The freeway that doesn’t exist. The spectral freeway.”

When we finally scraped ourselves off the road, we found the actual highway, of course, just over the hill, 0.2 miles from “the spectral freeway.” There was water cached there and each of us slugged a bottle.

What had happened is we misinterpreted the maps. So you can chalk that little episode up as user-error, I reckon; or we could all just enter a pact of secrecy and pretend it never happened at all. I’d be pretty cool with going that route, too, if that’s what you want to do.

Shhh. Don’t. Tell. Anyone.

Ahh, what an unexpected, fascinating joy this whole section was. I never knew it was here, you know. I mean, I never even knew any of this existed. And perhaps that’s just it. Maybe the act of continual discovery is what I love most about this walk.

And walking is meditative. It offers time to think about all sorts of things. For instance, one thing I’ve been thinking about is the “conquering” of the American frontier and the supposed affect this has had on the American psyche. It seems a popular notion in books about the West these days to bemoan the loss of the frontier, as if reaching the Pacific Ocean marked an endpoint in the nation’s collective endeavor to be explorational (that’s not a word, but by God it should be!).

There’s a part in the Red Pony by Steinbeck, for example, where an old man laments the loss of the American frontier.

“‘There’s no place to go,'” the old man says. “‘There’s the ocean to stop you. There’s a line of old men along the shore hating the ocean because it stopped them. Every place is taken. But that’s not the worst — no, not the worst. Westering has died out of the people. Westering isn’t a hunger any more.”

But I disagree, sort of — or, well, I just think it doesn’t have to be this way. There is so much to be seen and discovered within the bounds of our country. Just because a place is marked on a map doesn’t mean it isn’t terra incognita on a personal level. You don’t actually know a place till you go there, in other words. And while I wouldn’t argue that your average, modern-day American isn’t largely lazy, the opportunities for discovery are still there for those who are willing to take them. To understand this country in all its intricacies is an endeavor too complex even for an entire civilization of educated men and women. Some do make a valiant effort at comprehension, though — an important effort. Because the better we understand it, the better we can protect it. And, not to put too fine a point on it, but I see the Westering impulse in all of these thru-hikers I’ve met. I can sense it in their general joie de vivre. And it is infectious.

On the last night we tried to sleep amid a lightning storm and full-on deluge. In the morning the world smelled fresh and clean the way it does after a good thorough washing. We rose before dawn to egress through our final valley to the highway, and all the little rain droplets still clung to the twiggy branches of the sagebrush, dangling there like a hundred million diamonds draped on a hundred thousand necklaces. When the sun crested the craggy hills to the east, the entire valley glowed.

Scenes From the Trail

Cowboy Camping on a Mesa